The Homestead Act had a lasting effect on the American public consciousness and construction of history. However, scholarship and public opinion remain divided over its nature and effect on homesteaders and the United States as a whole. The public seems to consume the grand narrative of the Homestead Act, propagated by the popular media; scholars look at the meta-narrative of the legislation and its effects, leading to an entirely new debate. This debate over the Homestead Act finds itself now at a turning point: newly digitized records and new strategies for data analysis are leading to exciting opportunities for historical inquiry. Despite the rich opportunities allowed by data analysis, however, data-driven sources cannot replace experience-based sources in historical inquiry.

Scholarship regarding the success of the Homestead Act has a long, contested history. John Logie, writing for the Rhetoric Society Quarterly, claimed that the Homestead Act provided the framework for establishing vibrant communities on the frontier. “As these communities grew,” he argues, “the United States was greatly enriched by linking these former territories into its burgeoning economic structure.” In contrast, Lisi Krall states that the majority of homesteaders could barely scrape a living off of the barren land. Fred A. Shannon went so far as to claim that “[i]n its operation the Homestead Act could hardly have defeated the hopes of the enthusiasts of 1840-1860 more completely if the makers had actually drafted it with that purpose uppermost in mind.”

Scholarship, to a vast degree, has looked at the success of the Homestead Act by analyzing the Act as a whole. However, newly digitized records of individual homesteads that succeeded to ‘prove up’ provides an opportunity to analyze the nuances of that success. This opportunity proves necessary to take, as Shannon claims that “[the Act] tempted settlers out to the arid stretches where a quarter section was barely enough for the grazing of two or three cattle. Even where dry farming was possible, no family could exist on the product of 160 acres.” While earlier scholarship tells scholars who was able to prove up, until these records were digitized, said scholars did not know the circumstances or nuances of homesteaders’ lives beyond their acreage save for a few anecdotal accounts.

This project attempts to fill in some of these gaps in the research. By utilizing digitized records of homestead applications and approvals, this paper looks at trends among individual homesteaders with regard to how they chose to improve their homestead and set up their livelihood. Because Polk County receives an adequate rainfall every year for consistent crop growth, the majority of Polk County settlers decided to farm. Due to this fact, this paper used the amount of acres cultivated at the time of proof to indicate a baseline assumption of success as farmers. This is because the more acres a homestead was able to cultivate, the more crops they were objectively able to grow. While widespread bumper crops would have caused a decrease in success due to a decrease in demand, it is reasonable to assume that farming was difficult enough to establish in the first five years to make bumper crops rare.

The first measure this paper explores is the number of improvements listed on the homestead paperwork. To prove progress on their homestead, applicants had to explain what they had built on their land. In the case of Hiram Helvey, a settler in Polk County, the homestead consisted of a frame house, a barn, a corn crib, and a well (see Figure 1).

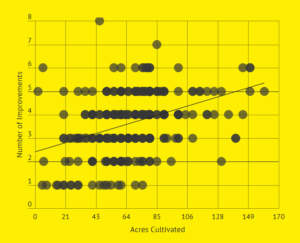

For this measure, Helvey’s number of improvements would have totaled four. With his 120 acres, Helvey would sit near the upper right corner of a scatter plot (see Figure 2). When added to the list of his peers, Helvey performs fairly well, but is underneath the trendline (see Figure 3).

The upwards-sloping trendline in Figure 3 shows a strong positive correlation between the amount of acres cultivated to the number of improvements made on a homestead. It is reasonable then to assume that the more improvements a settler made, the more successful they would become within the institution of homesteading. However, it seems remiss to only look at the number of improvements and not isolate the improvements, in case one improvement is significantly more valuable than the others.

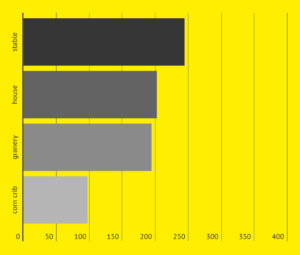

This next measure indicates how many settlers chose to build different improvements on their property (see Figure 4).

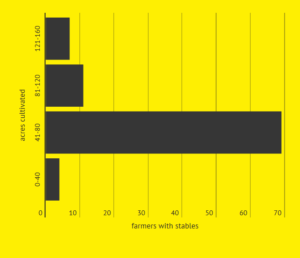

244 homesteaders in Polk County listed a stable on their property. However, as seen in Figure 5, the presence of a stable on the homestead does not seem to be a good indicator.

If the presence of a stable was a good indicator of success, the majority of stable-havers would have larger amounts of acres cultivated. However, Figure 5 indicates that most of the homesteads with stables only cultivated between 41-80 acres. While 41-80 acres seems like a large amount of acres to hand cultivate, when cross-referenced with Figure 3, it’s clear that many homesteads did in fact cultivate more than 80 acres, and thus the cultivation of 41-80 acres seems less significant. The median number of acres cultivated by farmers with stables was 70. This isn’t particularly exciting.

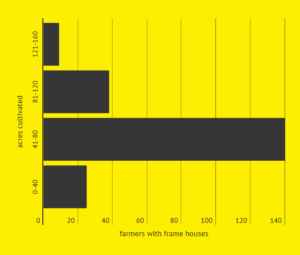

Because homesteaders had to prove residency, every settler listed a house on their property. However, the Fold3 data showed a distinction between a sod house and a frame house. Many people who built a sod house moved to build a frame house afterwards, and thus measuring the existence of a frame house against acres cultivated seems like it would narrow down the field to the most successful within the Homestead Act. However, looking at Figure 6, it’s clear that, again, the majority of homesteaders with frame houses cultivated 41-80 acres.

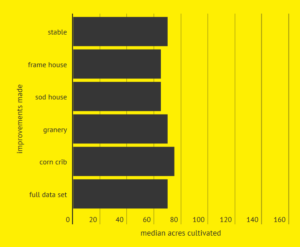

The median amount of acres cultivated by folks with frame houses is 65. In fact, looking at a variety of improvements listed within the Fold3 data, it’s clear that the median acres cultivated is fairly consistent – and fairly mediocre, at least proportionally to the possible acreage (see Figure 7).

So perhaps homesteaders were indeed considered successful if they cultivated 41-80 acres. This would be a situation where the reality of the perception of success would not be shown in empirical data. Another source to find this information is the compendiums of successful community members written by homesteaders. Utilizing a random sample of homesteaders who cultivated 41-80 acres, the compendiums were searched for mention of these homesteaders’ names.

Of the 10 homesteaders searched for in the 1899 Polk County Compendium, one appeared. John Wilson showed up in the biography of his father-in-law (see Figure 8).

It is important first to note that the compendium mentioned Wilson due to his relationships, not due to his farming achievements. This is mirrored when the text is analyzed (see Figure 9):

Of the words used in John Wilson’s biography, where he lived and his main relationship are the most important. The relationships of his children are also included, indicating the value of the institution of marriage on the frontier. While the compendium does give a description of Wilson’s property, he was not included in the compendium due to his farming accomplishments: it was his connections that established him as an important member of the community.

There was certainly a path to success on the frontier, and that was reflected by who was chosen to be mentioned in the compendiums. Some of the successful homesteaders went on to be doctors, legislators, and sheriffs. However, none of these people were particularly outstanding within the data collected from the digitized homestead records. It’s clear, then, that the measure of success used by the homesteaders was different than an analytical look at their accomplishments on their plots of land.

This makes sense. First off, homesteading was not the only way to success. Many people bought their land outright; these people tended to be wealthy when they went west, and thus were more likely to maintain their wealth than people moving west with nothing at all. Wealth provided many advantages that most homesteaders didn’t have, such as access to higher education, the ability to bail themselves out if there was a bad harvest, and the ability to open a business in town. These are the settlers who tended to become most successful (and featured in the compendium).

When homesteading did lead to success, that success was constructed in ways not celebrated by the data. The compendiums showed that homesteaders tended to laud their relationships over their farming-based accomplishments. While data can collect relationship-based information, it does not easily lend to picking successful people out of the group. The majority of the homesteaders this paper looked at could have been assigned family-based identities, such as father, sister, or child.

That’s not to say that homesteaders didn’t become successful through farming. However, the success they gained was likely to be shown through measures carefully chosen to represent the values frontier communities held. This idea, that what current scholarship considers success may not be what people in the past considered success, is vital to keep in mind when exploring new ways of gathering historical information. Data mining presents an exciting new methodology for finding trends and patterns beyond what historians can gather from a smattering of anecdotal evidence, but it cannot fully replace experience-based sources.

Little Clout on the Prairie: Perceived Success Within the Homestead Act of 1862 by Maria Peterson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.