Introduction

The Homestead Act of 1862 offered up to 160 acres of land to any member of the Union who was at least 21 years old and head of a household (Congress, 392) After five years of residing on the land and successfully cultivating the land for agricultural use and productivity, the settler could then file for ownership of their land claim. A successful homestead, then, has usually been considered to be any homestead that files and proves up its claim under the terms of the Homestead Act. However, few studies have attempted to define, analyze, and measure how successful various homesteaders were. This is because there are as many ways to define and measure what constitutes success as there were homesteaders. Based on homestead records from 364 distinct claims in Polk County, Nebraska, a database of information on ‘successful’ homesteaders was created. Statistically analyzing this data allows an attempt to be made to systematically model and predict the level of success based on factors such as age, household size, the presence of improvements, contributions by women, among others. For the purpose of interpretability in this study, acreage cultivated is used as a quantitative measure of success, as it is a measurement included on nearly all homestead claims in Polk County, and represents a tangible factor in productivity and physical ability.

Methodology

Data was collected by members of a class on homesteading and data visualization at Macalester College from records of individual homestead claims at time of proof and consolidated into a large dataset and spreadsheet. I performed statistical analyses using R and RStudio, a statistics and machine learning software. I first created binary variables out of the data on spouses and infrastructural improvements, and performed various regressions on the remaining and resulting variables. Initially, I performed exploratory analysis by plotting individual variables against each other, most notably various improvements and household size against acreage cultivated and age. From there, I performed single and multiple linear regression on the relationships that can be approximated linearly (as concluded from exploratory analysis). I then used cross validation methodologies to create the most powerful and accurate linear predictive model given the variables included (Shneider, 1).

Beyond linear regression and cross validation, there were two variables that showed some of the strongest relationships (and thus predictive potential) in modeling acreage cultivated, but exploratory analysis showed that their relationships were best approximated nonparametrically. I created visualizations for each of these variables individually and fit predictive nonlinear models (shown as approximated lines on graphs) for each of them. This is where my nonparametric analysis of the data met its limit, and thus future research should include pursuing the further predictive potential of nonparametric relationships with household size and age of claimant.

Analysis

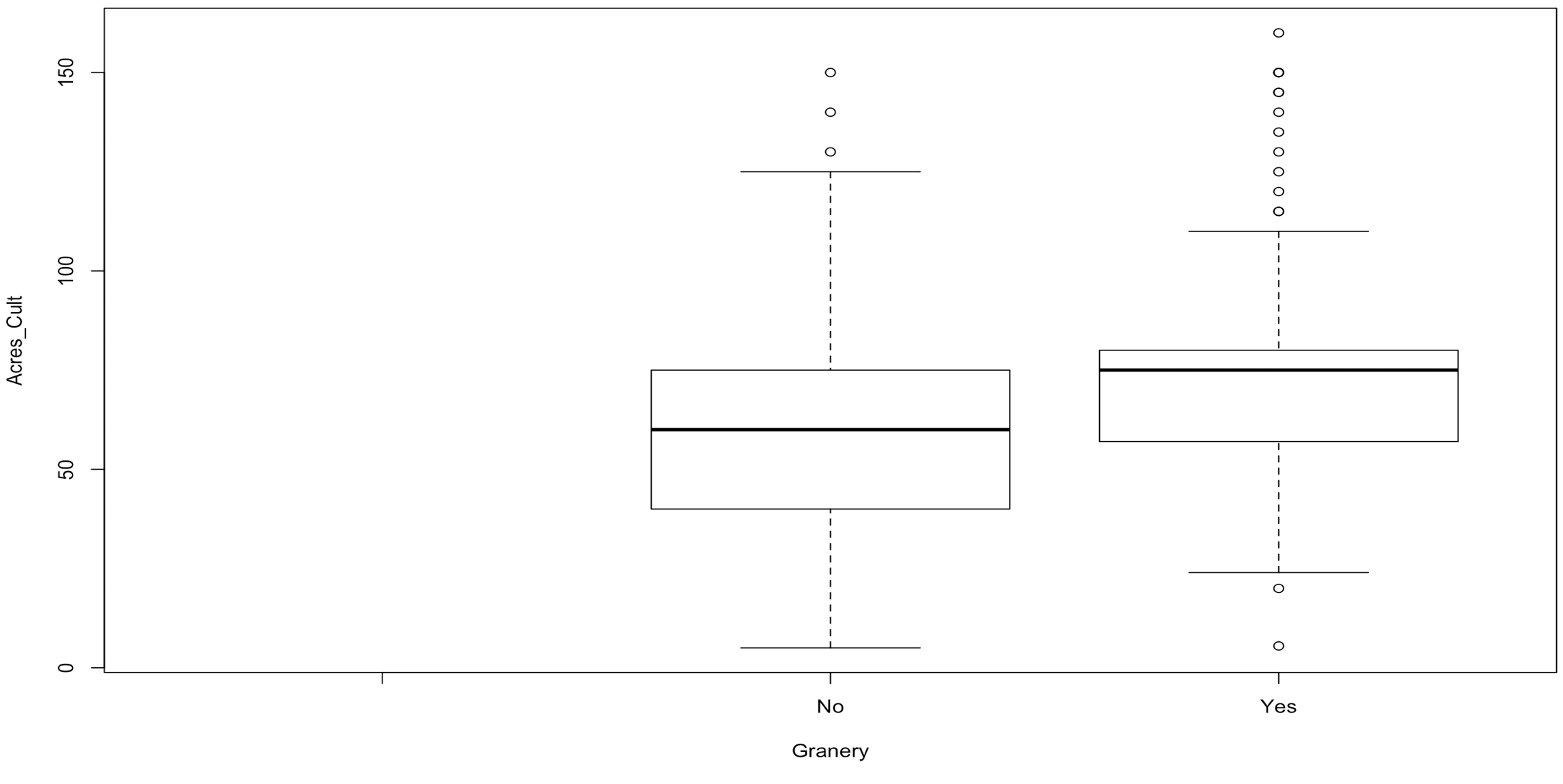

According to the data collected from Polk County homestead records, homesteaders who built a granary on average cultivated more land than those without granaries. This general trend is shown in Figure 1, a box-and-whiskers plot denoting spread, mean, and distribution of data. When considered alone and independently from all other predictor variables, the positive impact granaries seem to have had on homesteading success are very statistically significant. The results of this model are displayed in Table 1. Homesteads with other improvements, notably corn cribs and wells, also cultivated more acres on average than those without, but by a lesser degree. Each of these improvements can not be considered separately, as infrastructural improvements were built collectively and as needed. Moreover, too few instances of homesteads with possession of only a single type of improvement exist for statistical significance to be established. When considered collectively, only the presence of granaries showed a statistically significant improvement in model predictability among infrastructural improvements for acreage cultivated as a result of cross validation.

One particularly interesting line of inquiry revolves around the impact and importance of the presence of women on homesteads. It has long been assumed that homesteading and its associated physical labor were largely the domains of men, and that if women were present, they were “reluctant pioneers,” and their contributions were most significant in and immediately near the home, as opposed to in the fields (Cannon, 24). Regardless of the degree of truth of this assumption, women were present on many properties, and as contributors to the families and livelihoods of farms they made significant, though previously unverified, impacts on success (Webb, 118). Homestead records from Nebraska tell little if anything about the lives and significant contributions of women. Therefore, the exact methods in which women made contributions are unclear, and likely varied somewhat from homestead to homestead. However, through written records of accounts on the plains, such as Rachel Calof’s autobiographical narrative about her life on the North Dakota frontier, it is apparent that women worked intensively and laboriously to improve life on the farm and in the home (Calof and Rikoon, 42).

Figure 1: Presence of a Granary (Yes/No) vs Acres Cultivated

| Coefficients: | Estimate | P-value |

| Intercept // Granary | 58.976 | < 2e-16 |

| Granary Yes | 14.686 | 8.75e-06 |

Table 1: Modeling Acres Cultivated by Presence of Grainery

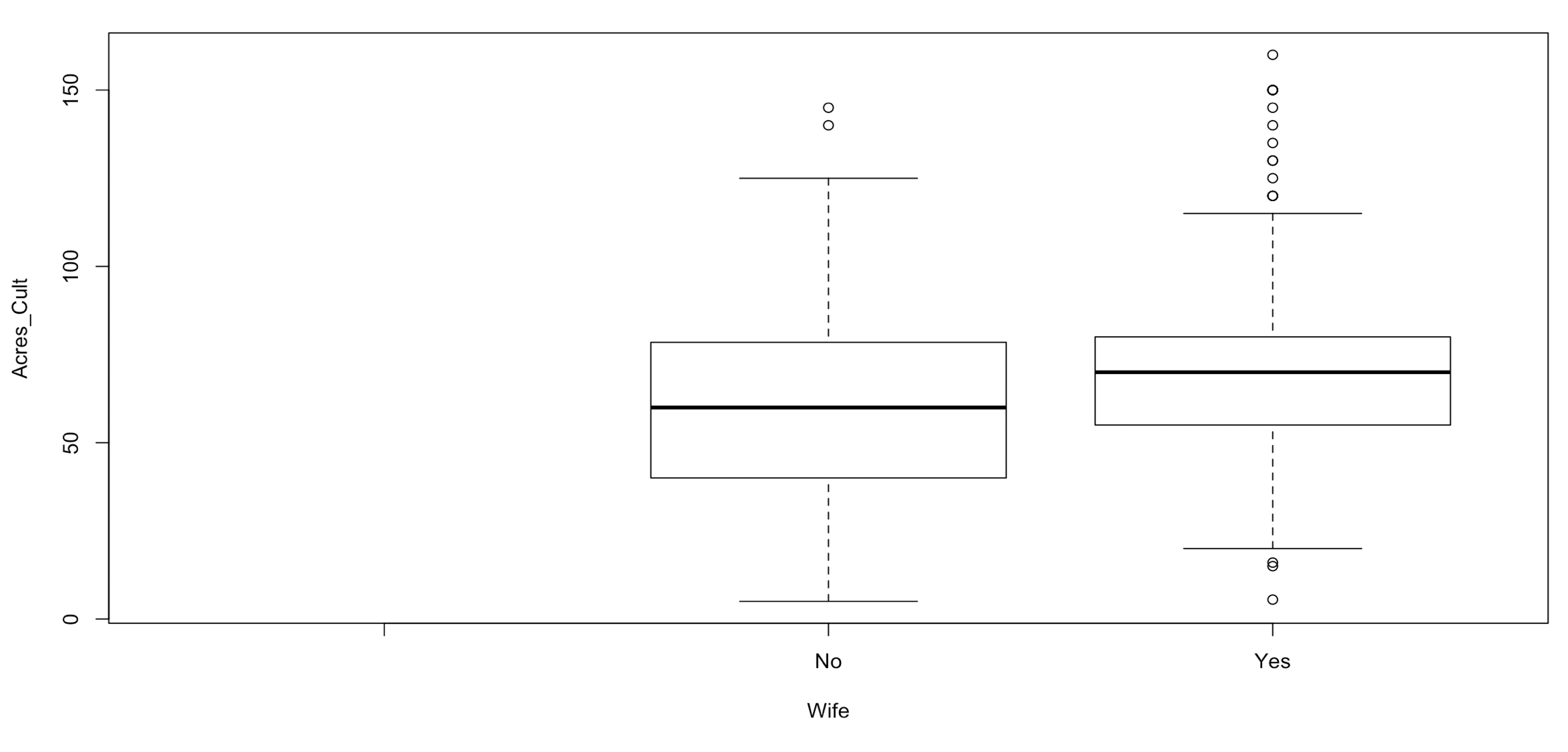

When measuring homesteading success by acreage cultivated, there is a positive relationship between the presence of women and total number of acres cultivated. While the homestead records from Polk County, Nebraska, rarely stated when women and wives were present on farms, the records do show whether or not the claimant has a partner and children. The presence of a wife on any individual claim can be easily inferred by taking note of all male claimants who listed themselves as being married and listed their families as including a spouse. Based on this distinction, this potential relationship can be visualized with a binary, box-and-whiskers plot of acreage cultivated against the presence of a wife. This is displayed in Figure 2, and shows that the mean acreage cultivated for homesteads with married partnerships is greater than the mean for those homesteads without. This relationship can be somewhat difficult to pinpoint visually, given the large range of values for acres cultivated. However, when modeled simplistically and individually, the positive impact women had on acres cultivated is statistically significant. This significance is represented in Table 2.

| Coefficients: | Estimate | P-Value |

| Intercept / No Wife | 60.719 | < 2e-16 |

| Yes Wife | 9.856 | 0.0105 |

Table 2: Modeling Acreage Cultivated by Presence of a Wife

Figure 2: Acres Cultivated vs Presence of Wife

Figure 2: Acres Cultivated vs Presence of Wife

People and variables seldom exist in vacuums. Independent variables can be confounding and/or interact with each other (Joseph, 1) . In the case of this homesteading data, having a wife on the homestead meant that work and improvements would have been done more swiftly and efficiently than if no person was present at home during the day. Thus, it is likely that the existence, quality, and quantity of infrastructural improvements was impacted by whether or not women were present on homesteads. In our example, having a wife could have had an effect on building and maintaining a grainery. Because of this, an interaction term between Granary and Wife should be included in a predictor model (Joseph, 1) . The results of the model that predicts Acres Cultivated based on the presence of granaries, wives, and their associated interaction is shown in Table 3.

| Coefficient: | Estimate | P-Value |

| Intercept (No Wife, No Granary) | 47.735 | < 2e-16 |

| Granary | 29.102 | 1.24e-05 |

| Wife | 17.105 | 0.00167 |

| Wife*Granary (Interaction) | -20.863 | 0.00614 |

Table 3: Modeling Acreage Cultivated by Presence of Granary and Women

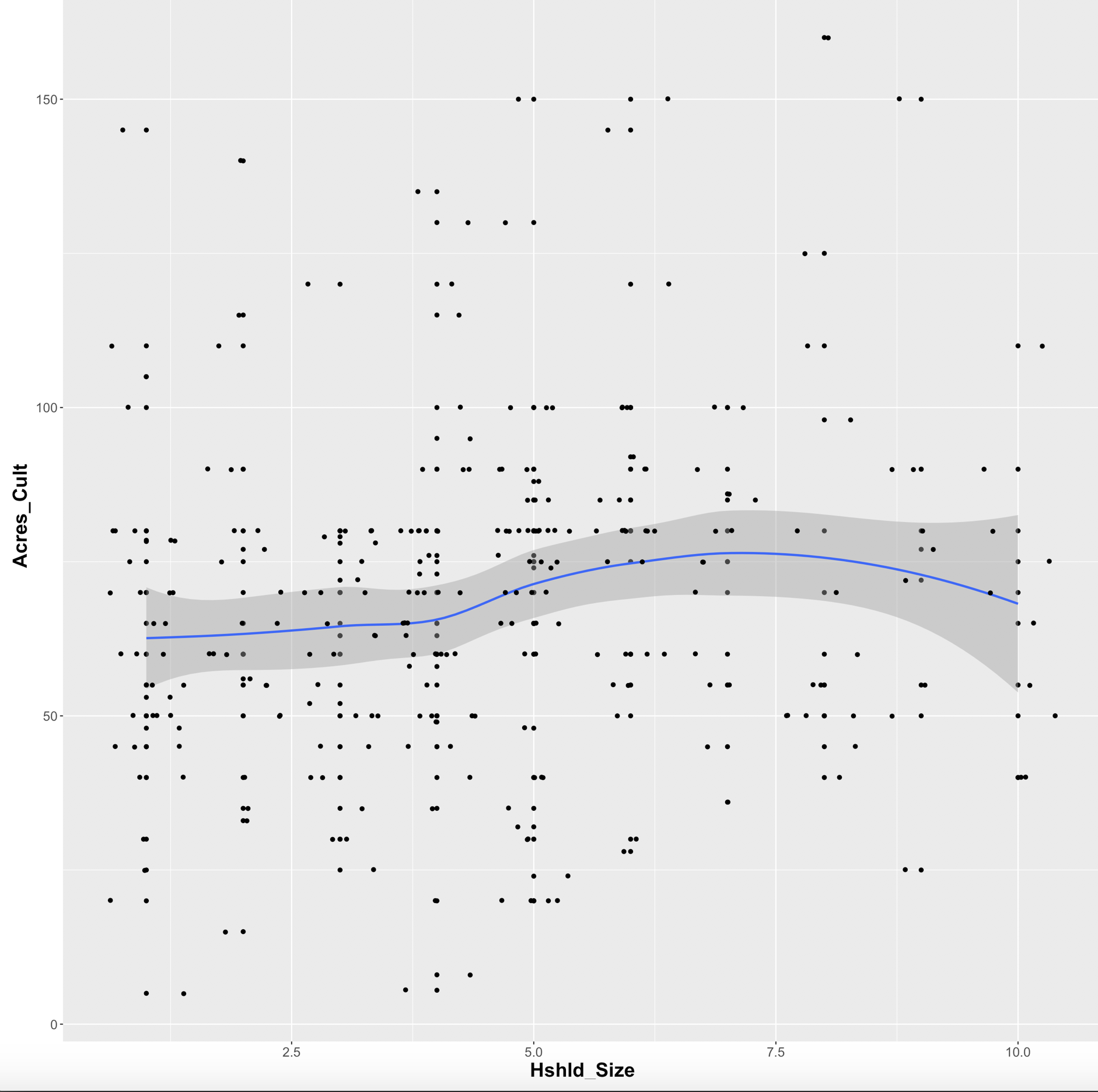

Another important observation of this analysis was the pattern and impact of household size and children on the acreage cultivated on homesteads. Generally, it might sometimes be assumed that having more children and thus more people residing and working on the farm tended to yield greater productivity and larger areas cultivated. Up to a certain family size, this seems to be true. Indeed, generally, homesteads with larger household sizes tend to cultivate more land than do small households. This is statistically significant, as displayed in Table 4. However, as shown in Figure 3, the relationship can be better represented nonparametrically. Note that households with 11 or more people were rare outliers, and thus have been excluded from the visualization. The pattern in the data seem to show a non-parametric, reverse parabolic relationship, instead of a truly linear trend. While it is true that households in the upper range of household size performed better than households in the lower range, peak acreage cultivated seems to occur with a household size somewhere between six and eight, corresponding to single families with four to six children. Thus, after this peak, the trend reverses and becomes negative.

Figure 3: Acres Cultivated as Predicted by Household Size

Note: The range in acres cultivated (y-axis) is far larger than the range in household size (x-axis), so the curved relationship is much stronger than is visually apparent.

| Coefficients: | Estimate | P-Value |

| Intercept (Hshld_Size = 1) | 60.3967 | -2e-16 |

| Hshld_Size | 1.8739 | 0.00489 |

Table 4: Linearly Modeling Acreage Cultivated by Household Size

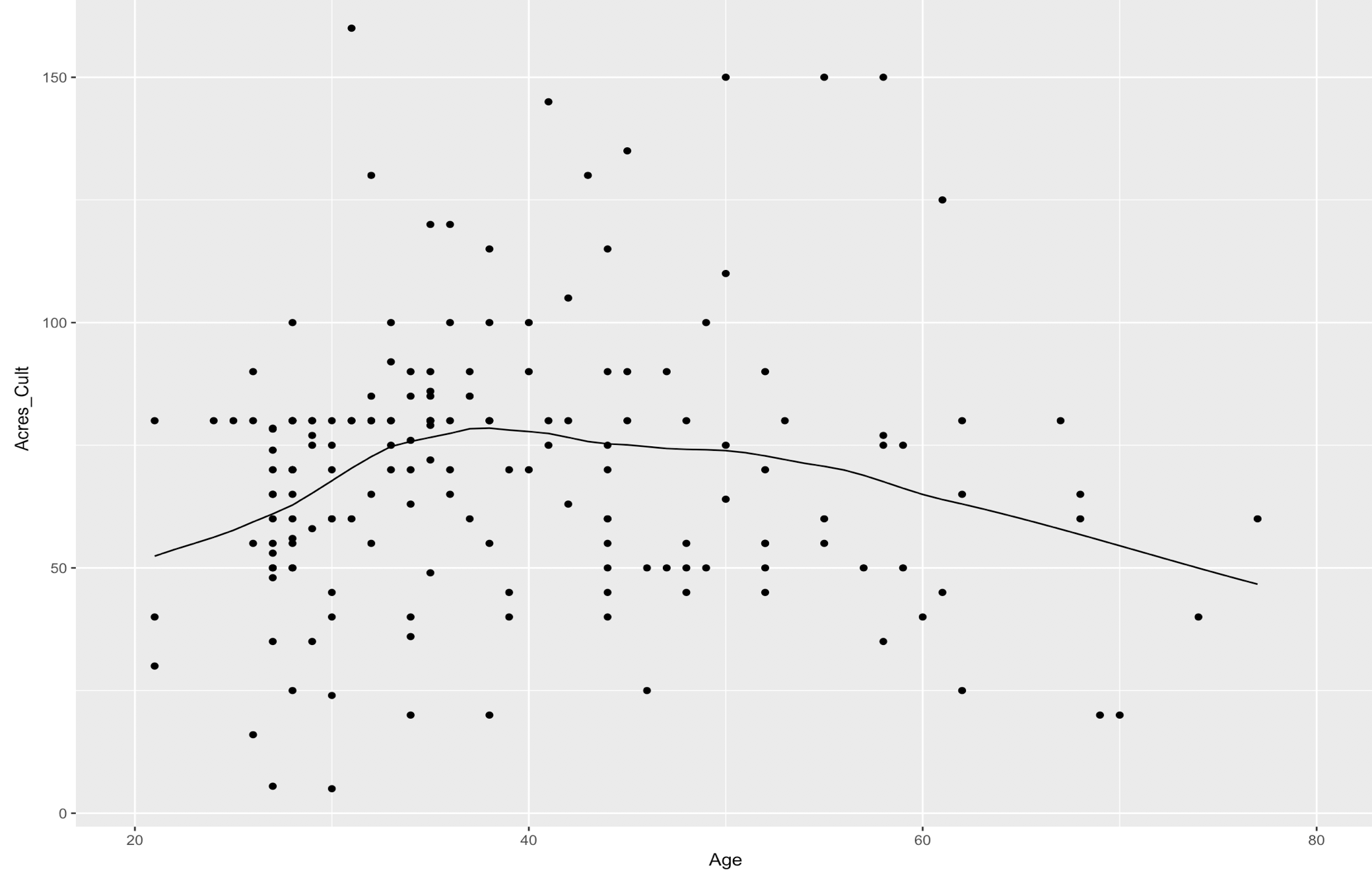

A similar nonparametric relationship is found between age and acreage cultivated, where the number of areas cultivated rises sharply between the ages of 20 and 35, and then levels off and steadily decreases after age 35 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Acreage Cultivated vs Age of Claimant

Conclusion

Based on the data collected from Polk County, there does not exist a single most powerful predictor in predicting acreage cultivated. However, it is true that there were several factors that were much more important than the others. Granaries, women and married partnerships played significant roles in improving cultivation and productivity on homesteads. Moreover, the presence of women/spouses on homesteads likely positively impacted the ability to develop infrastructure that in turn increased efficiency and productivity and thus acreage cultivated. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the relationship among household size, age, and acreage cultivated was not linear. More children and people on the farm was only beneficial up until around 5 to 6 kids on average, and for claimants beyond the age of 35, the ability to cultivate large amounts of land gradually diminished. The extent to which acreage cultivated decreased past these points of diminishing returns, however, remains uncertain, and beckons further study.

References

Bremer, Jeff. “Sod Busting: How Families Made Farms on the 19th-Century Plains.” The Annals of Iowa 74, no. 2 (2015): 196-97.

Cannon, Brian Q. Homesteading Remembered. Vol. 87. N.p.: Agricultural Historical Society, (2013): 1-29.

Calof, Rachel. Rachel Calof’s Story. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, (1995).

Congress, House, Homestead Act of 1862, Congressional Record (20 May, 1862); 392-393.

Joseph, Lawrence. “Interactions in Multiple Linear Regression.” McGill University.

Patterson-Black, Sheryll. “Women Homesteaders on the Great Plains Frontier.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 1, no. 2 (1976): 67-88.

Schneider, Jeff. “Cross Validation.” Carnegie Mellon University, (1997).

Modeling Acreage Cultivated for Homesteaders in Polk County, Nebraska by Everett Hommes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.