Snapshots of the Homestead Act

by Kevin Omodt

In 1862, the United States government passed the Homestead Act, which offered 160 acres of free land to heads of families as a way to further settle their newly acquired lands. This provided more than 1.5 million Americans with over 270 million acres of land, a fresh start across the Great Plains[1]. Recent efforts to further understand the history of the Act, along with the digitization of government records has aided a new effort to understand these homesteaders and the broader trends associated with them. These renewed efforts have revealed a newer understanding of the Act and its effects, spearheaded in part by researchers Richard Edwards, Jacob K. Friefeld, and Rebecca S. Wingo in their book Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History[2]. Using their data set from Dawes and Custer counites in Nebraska, along with new data gathered from Polk County records, available on fold3.com, we can see snapshots of homesteaders as they settled from East to West across the Nebraska plains. With these snapshots, we are able to examine the changes in our homesteader groups from the time of the Act, up to the early 1900’s. Through this, we are able to make generalizations about who the homesteaders, specifically immigrant homesteaders, were, where they came from and why, as well as immigration trends in the broader United States. We are also able to see patterns of settlement in our counties.

In our study area, the vast majority of claimants (n=991) were male, representing 92% of the group. This, however, does not show the whole picture of our adult claimants. Of these men, the vast majority of them were married. Of male claimants, 70% and 76% were married in Dawes and Custer, respectively, were married. This number is lower in Polk, however. The claimants in Polk were 95% male and of those men, 68% were married. One possible explanation is due to the earlier settlement of Polk, those drawn by the Act early on were single men looking for an opportunity, or those with families found it too difficult and gave up their claim. Based on Rachel Calof’s account of her homestead experience, it was a dismal life, especially early on. In general, however, this shows that while women made up only 8% of claimants, they were still a significant portion of homesteaders.

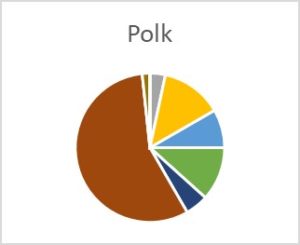

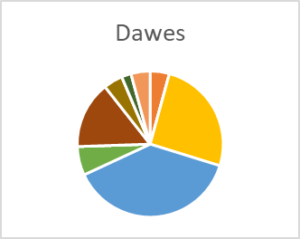

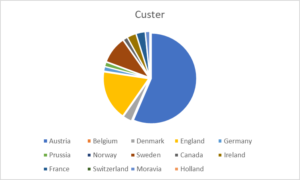

Another significant group were immigrants. All had become naturalized citizens, which was requirement of the act. They make up nearly 24% of all claimants. This is not as high as other states, such as Minnesota, Wisconsin and the Dakotas, where foreign-born farmers outnumbered native-born farmers, but it still makes up a large portion of homesteaders. Across the three counties, three immigrant groups are strongly represented. In Polk, Swedes are the dominant group. In Custer, it is the Austrians, and in Dawes, it is Germans. These populations may be the result of chain migrations, but they are part of broader immigrant trends that coincide with industrialization and change in each of these groups’ homelands.

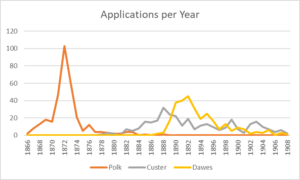

The counties have claims filed in different time periods, which can be used to look at push factors in the origin counties of these immigrants. In Polk County, the majority of claims were filed in the early 1870’s. This corresponds to a state of economic stagnation in Sweden in the 1860’s, and an ensuing industrial revolution. This left traditional farmers in the country facing low wages, during a time where America offered higher wages and opportunity. From 1850-1890, more that 1 million Swedes came to the United States[3]. Similarly, the Austrians of Custer County were pushed by economic forces, albeit a few years later. The majority of claims in Custer County were filed from 1886 to 1899 and previous to this, Austria had faced the first global stock market crash, which lead to an international depression, which lasted from about 1873 to 1880[4]. For the Germans of Dawes county, they were likely driven by the changing political climate, which lead to economic change in the country. After the unification of Germany in 1871, there was both political change, but also rapid industrialization. It is highly likely that all three cases, the traditional farmers of these European nations were pushed out of livable wages the large-scale privatization and industrialization of farming, which required fewer laborers per acre of farmland. The alternative in America not only provided the opportunity for higher wages, but also the ability to become a land owner for a small initial cost.

In my analysis, I used R studio, a data-focused language, to isolate and look at the data specifically relating to immigrant groups. The records used to create the data came from a conglomeration of entities who are digitizing the records held by the National Records and Archives Administration (NARA). This group includes the NARA, the University of Nebraska, the Homestead National Monument of America, fold3.com, and familysearch.com. The data for Dawes and Custer Counties were gathered by the researchers who wrote Homesteading the Plains, as well as having some collaboration from Richard Lang, an independent scholar whose research was used to identify townships within these counties where homesteading was common. The Polk County data was gathered from fold3.com by group of students at Macalester College of which I was a part. The data only includes those homesteaders who were able to prove up on their claims, so those who failed are not included in the data set. The data, however, is a complete look at every successful homesteader in each of the townships studied. This allows us to be definitive in our conclusions about the data. Unfortunately, we found some limitations in our Polk County data, as the questionnaires, which were still under development, did not have the same information, such as improvement value or state of origin. In these cases, certain data like age or state of origin were only found through military records.

Based on this figure, we can see that our homesteaders came to Polk County in greater numbers first, and this likely is a result of Polk being the furthest east, but also it is east of the 100th meridian, which is where the eastern, more humid climate transitions to a drier one. This could be an explanation for the settlement patter that we see, with Polk being settled first and more rapidly, but it is unlikely. Although important to farmers, it is doubtful that our homesteaders were acutely aware of weather, and more likely that the patterns of application were more influenced by simple proximity. The townships surveyed in Polk County are directly adjacent to one another, whereas the townships surveyed in Dawes and Custer are more scattered within their respective counties. It would be interesting to see if the people in Polk’s sample area are more connected via family and ethnic ties, as further research could reveal that having these connections brought settlers to these nearby townships at a quicker rate.

Our snapshots of these counties have allowed us to look at changes in Nebraska’s homesteaders over time, and this has left us with several conclusions. Firstly, it is important to recognize that a lot of previously held conclusions are true when it comes to general demographics: Women made up a significant portion of adult homesteaders, but do not often appear in forms as claimants, but rather as spouses. Secondly, Nebraska is a state with a notable immigrant population, but they are not near the majorities held by immigrants, based on samples, in places such as Minnesota. This population, however, gives us an idea of broader immigration trends in the United States at the time, and we can pretty well identify the push factors that brought them to the America. Lastly, we can see the rapid rate at which Polk County was filled compared the other two, but this seems to be a result of the adjacency of our sample area and chain migration rather than aggressive land grabbing. This in particular would be worth researching as it could provide a number of different results. With the high concentrations of individual immigrant groups, this would lead us to believe that chain migration is in part responsible for more rapid settlement, but it difficult to say for certain, as we have high concentrations in all three of our sample areas. With further research of our counties, we would be able to examine adjacent townships in across our counties and compare both the rate of settlement and concentration of immigrants or familial ties in these adjacent groups. If correlation exists between these three factors, we would be able to make a stronger assertation about the existence of chain migration.

[1]2017. In Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History, by Richard Edwards, Jacob K. Friefeld and Rebecca S. Wingo, 7. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

[2] Edwards, Richard, Jacob K. Friefeld, and Rebecca Wingo. 2017. Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

[3] Akenson, Donald Harman. 2011. Ireland, Sweden, and the Great European Migration, 1815-1914. Montreal: McGill-Queen University Press.

[4] Glasner, David, and Thomas F. Cooley. 1997. Crisis of 1873. Taylor & Francis.