In May 1862, the Homestead Act granted men and women across the United States 160 acres of public land for a minimal fee and 5 years of settlement. Homesteaders like notable Rachel Calof, a Russian woman who came to the U.S. to marry a homesteader, rushed to the plains with little food, fuel, or money, hoping to cultivate a successful farm. Calof described her experiences in Rachel Calof’s Story, a memoir published by her daughter years after Calof’s death in 1952.

One of the prevailing themes of Rachel Calof’s Story, and the stories of many other homesteaders, is perseverance–while facing a “moment-to-moment battle” for survival, she finds the strength to care for her children, herself, and her household chores in order to keep the family afloat (Calof 86)

While stories such as Rachel Calof’s recount homesteader struggles in detail, few historians have analyzed the outside factors that impacted homesteader success on the plains. Despite the current data preventing the inclusion of homesteaders who failed to prove up, or stay on their land for the required five years in order to keep it, this paper will predict the ability of successful homesteaders to achieve the main goal of the homestead act–land cultivation–by analyzing nearly 400 land claim documents in Polk County Nebraska. This paper determines that marital status, immigration status, and number of children were the best predictors of a claimant’s ability to farm successfully on the plains.

Impact of Children on Homesteading Success

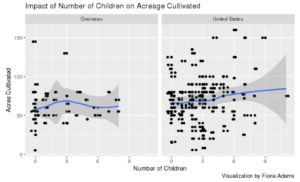

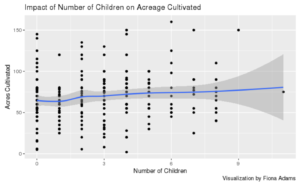

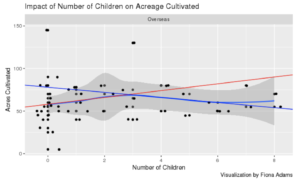

Children, on average, impacted homesteading in a positive way. Historians such as Anne B. Webb and Sheryll Patterson-Black have suggested that “the life of a single woman, or at least the childless one, was a cut above her married sister” because a single woman could devote more energy to her own long-term survival, while a woman with a large family had to constantly focus on her children (Patterson-Black 74). However, in many families, children of both sexes started doing field work and cross-country errands at an early age–usually by nine or ten. Their chores included helping with the planting, hoeing, and harvesting; herding cattle; hauling feed, fuel, and water; trading at local stores; and taking crops to market (Harris 45). Our data reflected that work, showing that the addition of 1 child to a homesteading family enabled them to cultivated 1.65 more acres, as shown by the graph below.

Despite their significant impact on land cultivation, children had little to no effect on the type or number of improvements a family was able to make. This is likely because, at their young age, children did not have the technical skills to help with hard tasks such as building a frame house. This is also made clear by Harris’ listing of typical children’s chores; planting, harvesting, herding, and trading are all relatively low-impact and low-skill tasks that would not augment the family’s ability to improve their homestead’s economic value. While these tasks did not make it onto the proof statements, having these daily necessities out of the way would certainly allow the parents to focus on farm cultivation and housework, leading to that addition of 1.65 acres cultivated seen above. When we take marital status into account, the impact of children is even clearer.

Despite their significant impact on land cultivation, children had little to no effect on the type or number of improvements a family was able to make. This is likely because, at their young age, children did not have the technical skills to help with hard tasks such as building a frame house. This is also made clear by Harris’ listing of typical children’s chores; planting, harvesting, herding, and trading are all relatively low-impact and low-skill tasks that would not augment the family’s ability to improve their homestead’s economic value. While these tasks did not make it onto the proof statements, having these daily necessities out of the way would certainly allow the parents to focus on farm cultivation and housework, leading to that addition of 1.65 acres cultivated seen above. When we take marital status into account, the impact of children is even clearer.

Impact of Family Size and Marital Status on Homestead Success

Homesteader improvements varied by marital status, with married couples able to achieve more physical infrastructural improvements and seeing a more prominent “tipping point” in how much their children helped them cultivate. When it came to infrastructural improvements, marital status made a very noticeable difference. If a single person got married between filing and proving up, their chances of having a sod house decreased by 21%. But, if a married person was widowed during their five year occupancy on the land, their chances of having only a sod house increased 18%. Sod houses were a cost-effective way for homesteaders to create their first residence, but were far from comfortable. Relying on the top layer of earth known as “sod,” one of the only readily available building materials on the plains, was incredibly work-intensive–cutting sod without mechanized instruments took days, and the material had to be used immediately to avoid crumbling and drying (Ankli 55). Thus, as 1902 homesteader Ruth Hall explained, a house made with a wooden frame was a “luxury after years in a little sod house” (Harris 47). As we saw above, both male and female homesteaders had a much higher chance of building frame houses when married–whether a homesteader was gaining a husband or a wife, their ability to create a more comfortable environment was only heightened once they had a partner.

These little luxuries extended to other improvements; 79% of married couples had a well, while only 50% of single people had one and 43% of widows had one. However, if a single person got married between filing and proving up, their chances of having a well (a great physical feat) increased 20%. The fact that a spouse led to such an essential difference in improvement value is not surprising–these statistics were heavily influenced by the 340 men in our dataset, who welcomed a wife as an essential economic contributor, both in the home and outside of it. In addition to women’s contributions within the homestead and out on the farm, author Katherine Harris explains that butter and eggs from the chickens women raised were “two of the most important elements of the domestic economy, for money received from their sale was sometimes the only cash income a family had” (Harris 45). Due to these contributions, scholar Sue Armitage of the Montana Historical Society even goes as far as to say that “men could not have afforded to farm or ranch without the work of women in their lives” (Armitage 7).

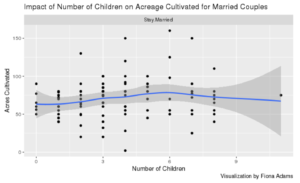

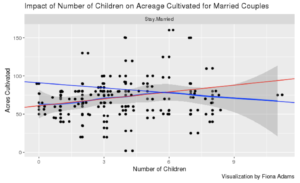

When influenced by number of children, marital status had a profound impact on acreage cultivated. As seen in the graph above, couples who stayed married between filing and proving up saw a clear “tipping point” in the ability to cultivate acreage. Five or fewer children improved farm production; any more negatively impacted acreage cultivated. Each child helped the family gain 3.1 acres of cultivated land until that tipping point, after which each child decreased the acreage by 2.20–a clear difference from the 1.65 acres each child added to the average homesteader’s cultivated acreage (that is, without the control for marital status). The visualization below shows these values fitted onto the graph, the red line showing the impact of children up until the tipping point, and the blue line showing the decrease in acreage cultivated after a certain number of children. Despite this clear tipping point in acres cultivated, there was no similar change in the infrastructural improvements made for married couples with different numbers of children, just as we saw earlier with data on homesteaders overall.

When influenced by number of children, marital status had a profound impact on acreage cultivated. As seen in the graph above, couples who stayed married between filing and proving up saw a clear “tipping point” in the ability to cultivate acreage. Five or fewer children improved farm production; any more negatively impacted acreage cultivated. Each child helped the family gain 3.1 acres of cultivated land until that tipping point, after which each child decreased the acreage by 2.20–a clear difference from the 1.65 acres each child added to the average homesteader’s cultivated acreage (that is, without the control for marital status). The visualization below shows these values fitted onto the graph, the red line showing the impact of children up until the tipping point, and the blue line showing the decrease in acreage cultivated after a certain number of children. Despite this clear tipping point in acres cultivated, there was no similar change in the infrastructural improvements made for married couples with different numbers of children, just as we saw earlier with data on homesteaders overall.

Impact of Immigration Status on Farming Success

Immigrants saw the most significant impacts to their ability to cultivate and improve their land when they had children. Natural born homesteaders had “home field advantage,” cultivating an estimated 114 acres and achieving an 1.4 additional acres per child, only slightly less than the average impact of 1.65 acres. Immigrants, on the other hand, cultivated only an estimated 48 acres and saw a large tipping point in acreage cultivated.

As seen in the visualization above, immigrants were able to cultivate an additional four acres per additional child until they had three, at which there was a tipping point, and they cultivated three fewer acres per additional child. The visualization to the left shows these trends mapped. It is clear to see that while natural born citizens saw a more linear impact of household size changes, immigrants saw a big dip after having more than three children, signifying that children were more of a liability to immigrant families than to natural born ones. U.S. citizens with children and immigrants with children both had the same median age of 35, so it is unlikely that immigrants had younger children, and thus less ability to put their children to work. This means that facing the same circumstances of age and marital status, there is a striking difference between success for natural born and immigrant homesteaders. There are many possible reasons for this–while both natural-born citizens and immigrants had the same median number of witnesses on their proof statements, work by my colleagues Esther Ramsay and Lukas Matthews revealed that immigrants in our dataset either settled close together or were relatively isolated both geographically and socially, meaning many would be unable to rely on their neighbors as much as someone with nearby family members and closer ties to the language and culture of the United States.

shows these trends mapped. It is clear to see that while natural born citizens saw a more linear impact of household size changes, immigrants saw a big dip after having more than three children, signifying that children were more of a liability to immigrant families than to natural born ones. U.S. citizens with children and immigrants with children both had the same median age of 35, so it is unlikely that immigrants had younger children, and thus less ability to put their children to work. This means that facing the same circumstances of age and marital status, there is a striking difference between success for natural born and immigrant homesteaders. There are many possible reasons for this–while both natural-born citizens and immigrants had the same median number of witnesses on their proof statements, work by my colleagues Esther Ramsay and Lukas Matthews revealed that immigrants in our dataset either settled close together or were relatively isolated both geographically and socially, meaning many would be unable to rely on their neighbors as much as someone with nearby family members and closer ties to the language and culture of the United States.

Conclusion

By analyzing the proof statements of Nebraska homesteaders, we can determine that marital status, immigration status, and number of children were the best predictors of success on the plains. The final statistical model, showing the impact of marital status at time of filing and after proof, country of origin, and number of children on acres cultivated, reveals a clear change in success rates when different factors are involved. For example, a married woman who became a widow could cultivate 29.13 acres, but every child she had helped her cultivate 13.5 more–showing the big impact of children on the livelihoods of women homesteaders. Similar patterns emerge with immigration–an immigrant could cultivate an estimate of 48 acres, while a natural born citizen could cultivate 114.

These patterns are further elucidated in the “Predict My Homesteading Success” tool shown below. For more information about the statistics behind those models, please click here.

Methodology

I chose to define “family success” through acreage cultivated. While the definition of success was limited by the data we could collect from proof statements, the fact that one of the main goals of the Homestead Act was for families to occupy and cultivate their claim for five years, made this an apt definition (Bradsher 27).

I then used an elimination method to create a model of Acres Cultivated by all possible factors, including Sex of Original Claimant, Year of Filing, Number of Witnesses Used in Proof Papers, State of Origin, Age, Marital Status at Time of Filing, Marital Status at Time of Final Proof, Sum of Marital Status (to create a sum of marital status, I joined together the claimant’s marital status at time of filing and the marital status at time of final proof, such as Married.Married and Married.Widow), Household Size, Number of Children, Number of Crops, Trees Planted (written Yes or No, because many homesteaders wrote their improvements as “a few” trees rather than a number), Number of improvements, and Country of Origin. Once narrowing the model to only the statistically significant values (alpha >= 0.05, in this case), I found that Sex, Country of Origin (United States versus abroad), and Number of Children were the best predictors for Acreage Cultivated.

Database Limitations

Despite the excitement that raw data brings to the study of homesteading, the land claim data cannot be applied to all homesteaders who attempted to cultivate land in Polk County Nebraska. The many failed claims, as well as fraudulent claims, are not accounted for in our dataset, despite fewer than 50% of homesteaders proving up on their land (National Park Service). This is because public record only includes successful claims, and claimants commonly listed the improvements they made, rarely the struggles they faced along the way. Despite these limitations, our dataset revealed many statistically significant findings about the predictors of success on the plains. In future, an analysis of the homesteaders who failed to prove up would be a valuable exploration.

Stuck in a Sod House: The Impact of Family Structure on Homestead Value by Fiona Adams is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.